Tuesday, February 16th, 2010

On Joshua Clover’s 1989

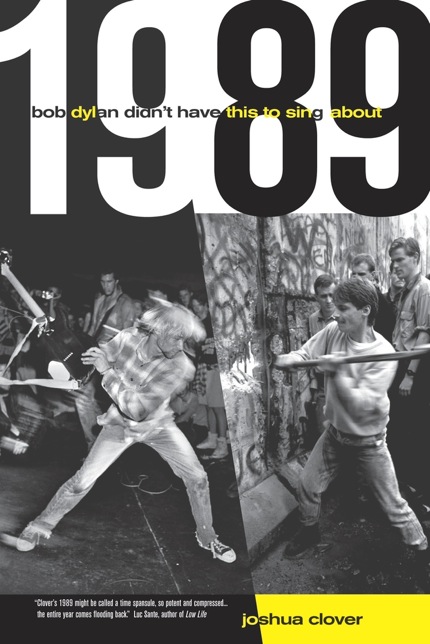

From the latest issue of The Progressive, here’s a teaser for my review of Joshua Clover’s new book 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This To Sing About:

What can popular music really do? Can it topple walls, stop tanks, unleash hope and change? Or are those powers really just a mass delusion, simply another part of the sale? For centuries the question of culture’s influence has occupied poets, philosophers, even those disposed to the sordid arts of politics. At the start of a new decade, poet-philosopher-activist Joshua Clover finds them worth reexamining in his dense, provocative, wonderfully written little book, 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This To Sing About.

In 1989, the scope of global events suggested political change on a scale unseen since 1968. The new expansiveness in pop music seemed to sound out a perceptual change as well. Something new was happening in what Clover calls “the unconfined, unreckoned year,” but exactly what?

Forests of hagiographies have long since taken the riddle and blood out of 1968. 1989 presents a different kind of capstone, one that leaves the left in a quandary. For the 1980s were the decade that the North American left never wanted. They remain critically under-examined, as if they were better forgotten.

But in neocon narratives, those years are carried as if on a wind of inevitability. Borrowing Raymond Williams’s startling turn of phrase, Clover is interested in describing “structures of feeling.” And the feel of 1989 was captured by Francis Fukuyama’s wacky “end of history” thesis, in which he posited from cascading global events that history had finally collapsed into the eternal truth of “the Western Idea”—World Liberal Capitalism (itself the flattening of two different subjects, “liberal democracy” and “global capitalism”).

Intellectuals love “end of” narratives: “the end of liberalism,” “the end of Black politics,” “the end of irony.” But these stories, even when nostalgic and ridden with regret and loss, are almost always rigid and triumphal. Clover takes this as a given. To him, the fact that history did carry on after the Fall of the Berlin Wall is barely worthy of comment (although this means he also misses an opportunity to cite the lyrics of Soul II Soul’s fine ’89 hit, “Keep On Movin’ ”).

But the popularity of certain “end of” narratives fascinates him, because they capture a mass consciousness, “a way of knowing.” Clover links the functions of pop music and what might be called pop history. So OK, it may be true that we live in an age of iPod isolation where smart pop criticism has retreated into microgenre formalism and an age of tabloid capitalism where the cult of celebrity eclipses even the most fashionable forms of materialist analysis. (These phenomena may be better known by their names “The iTunesification of Everything” and “The Cornel West Dilemma.”) But Clover doesn’t allow the reader to sweep all of that into a dustbin called “false consciousness” and walk away from the masses. Instead, he wants to clarify the real stakes of culture.

Clover is an acclaimed poet who may be best known for his music and film criticism. He is also an 89er who was shaped indelibly by the left movements of the era—from anti-apartheid and Central American solidarity to the AIDS crisis and anti-racism to the anti-corporate globalization movements. (Most recently, he has been a key faculty leader in the broad movement against the University of California’s budget cuts and fee increases.) But Clover holds serious doubts about pop music’s ability to “herald a new political awareness,” the notion—to borrow (and tweak slightly) Jacques Attali’s famous dictum—that music can be prophecy…

+ Buy the magazine or subscribe here.

+ Buy the book here.

posted by Jeff Chang @ 5:46 am | 1 Comment

One Response to “On Joshua Clover’s 1989”

Previous Posts

- Who We Be + N+1=Summer Reading For You

- “I Gotta Be Able To Counterattack” : Los Angeles Rap and The Riots

- Me in LARB + Who We Be Update

- In Defense Of Libraries

- The Latest On DJ Kool Herc

- Support DJ Kool Herc

- A History Of Hate: Political Violence In Arizona

- Culture Before Politics :: Why Progressives Need Cultural Strategy

- It’s Bigger Than Politics :: My Thoughts On The 2010 Elections

- New In The Reader: WHO WE BE PREVIEW + Uncle Jamm’s Army

Feed Me!

Revolutions

- DJ Nu-Mark :: Take Me With You

DJ Nu-Mark remixes the diaspora…party ensues! - El General + Various Artists :: Mish B3eed : Khalas Mixtape V. 1

The crew at Enough Gaddafi bring the most important mixtape of 2011–the street songs that launched the Tunisian & Egyptian Revolutions… - J. Period + Black Thought + John Legend :: Wake Up! Radio mixtape

Remixing the classic LP w/towering contributions from Rakim, Q-Tip + Mayda Del Valle - Lyrics Born :: As U Were

Bright production + winning rhymes in LB’s most accessible set ever - Model Minority :: The Model Minority Report

The SoCal Asian American rap scene that produced FM keeps surprising… - Mogwai :: Hardcore Won't Die But You Will

Dare we call it majestic? - Taura Love Presents :: Picki People Volume One

From LA via Paris with T-Love, the global post-Dilla generation goes for theirs…

Word

- Cormac McCarthy :: Blood Meridian

Read this now before Hollywood f*#ks it up. - Dave Tompkins :: How To Wreck A Nice Beach

Book of the decade, nuff said. - Joe Flood :: The Fires

The definitive account of why the Bronx burned - Mark Fischer :: Capitalist Realism

K-Punk’s philosophical manifesto reads like his blog, snappy and compelling. Just replace pop music with post-post-Marxism. Pair with Josh Clover’s 1989 for the full hundred. - Nell Irvin Painter :: The History of White People

Well worth a Glenn Beck rant…and everyone’s scholarly attention - Robin D.G. Kelley :: Thelonious Monk : The Life And Times Of An American Original

Monk as he was meant to be written - Tim Wise :: Colorblind

Wise’s call for a color-conscious agenda in an era of “post-racial” politics is timely - Victor Lavalle :: Big Machine

Victor Lavalle does it again!

Fiyahlinks

- ++ Total Chaos

The acclaimed anthology on the hip-hop arts movement - ARC

- Asian Law Caucus | Arc of 72

- AWOL Inc Savannah

- B+ | Coleman

- Boggs Center

- Center For Media Justice

- Center For Third World Organzing

- Chinese For Affirmative Action

- Color of Change

- ColorLines

- Dan Charnas

- Danyel Smith

- Dave Zirin

- Davey D

- Disgrasian

- DJ Shadow

- Elizabeth Mendez Berry

- Ferentz Lafargue

- Giant Robot

- Hip-Hop Theater Festival

- Hua Hsu

- Humanity Critic

- Hyphen Magazine

- Jalylah Burrell

- Jay Smooth

- Joe Schloss

- Julianne Shepherd

- League of Young Voters

- Lyrics Born

- Mark Anthony Neal

- Nate Chinen

- Nelson George

- Okay Player

- Oliver Wang + Junichi Semitsu :: Poplicks

- Pop + Politics

- Presente

- Quannum

- Raquel Cepeda

- Raquel Rivera

- Rob Kenner

- Sasha Frere-Jones

- The Assimilated Negro

- Theme Magazine

- Toure

- Upper Playground

- Wayne Marshall

- Wiretap Magazine

- Wooster Collective

- Youth Speaks

@zentronix

- No public Twitter messages.

Come follow me now...

Archives

- July 2014

- May 2012

- January 2012

- June 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- November 2003

- October 2003

- September 2003

- August 2003

- July 2003

- June 2003

- May 2003

- April 2003

- March 2003

- February 2003

- January 2003

- December 2002

- November 2002

- October 2002

- September 2002

- August 2002

- July 2002

- June 2002

We work with the Creative Commons license and exercise a "Some Rights Reserved" policy. Feel free to link, distribute, and share written material from cantstopwontstop.com for non-commercial uses.

Requests for commercial uses of any content here are welcome: come correct.

This paragraph kills me (literally):

“So OK, it may be true that we live in an age of iPod isolation where smart pop criticism has retreated into microgenre formalism and an age of tabloid capitalism where the cult of celebrity eclipses even the most fashionable forms of materialist analysis.”